DEMYSTIFYING THEORIES OF CHANGE AND PROGRAM LOGICS

Do theories of change and program logics excite you or bore you? Are you overwhelmed by them, or maybe don’t see what all the fuss is about?

My observation from the people I have worked with has been quite variable. Some people love a clearly articulated theory of change, and can’t wait to see the outcome of its implementation; whilst others are a bit confused, and might slink down in their chair when asked to describe their program or intervention’s theory.

For those in the first group… me too !! I love a good theory, and get excited about the prospect of testing it, learning from the results, making some adjustments, and then testing again. Monitoring and evaluation in action – beautiful!!

For those in the second group… chances are you probably understand parts if not all of the theory that underpins your program or intervention, but maybe implicitly… and maybe you’ve just never been asked the right questions to make it explicit.

A theory of change, or the theory or theories that underpin your program or intervention, help to explain why the program has been designed and is delivered in a certain way, and how the program is thought to bring about the desired outcomes.

The design of a program is informed by someone’s knowledge (hopefully). This knowledge may have come from formalised study, reviewing the literature, previous experiences, cultural beliefs… and may be a mix of fact, opinion or assumptions.

Guided by this knowledge, we make decisions about how to design and implement our programs, with the strong hope that they lead to our desired outcomes.

- Maybe a weight-loss program, smoking-cessation program or anger-management program is informed by social learning theory, or behaviour modification theories.

- Maybe the way we design and implement training programs to improve employment opportunities is based largely on adult learning theories, which may have been tweaked or adapted based on our learnings from previous experiences.

- Maybe we design our communication and engagement activities to take advantage of social network theories.

- Maybe we ensure that our clients always have a choice about the gender of their clinician, or the location or modality of their sessions, because we know that the strong rapport between client and clinician is a good predictor of positive outcomes.

Some of the knowledge we use to inform our programs, activities and interventions may be based on long-standing, strongly-held, widely-acknowledged theories, such as attachment theory or social learning theory, whereas other knowledge may have emerged very recently from our own observations, or reflective practice, or careful monitoring of our programs. Regardless of whether your theories have emerged from formalised training, a review of the literature, your previous experiences and observations, or your cultural beliefs – they are all still theories that guide and explain the assumptions behind why you think your program will achieve the desired outcomes.

The implementation of your program is really just testing to see if the theory is correct. Hopefully you’ve employed some rigour, and consulted broadly to ensure you’ve made good decisions in your program design, to optimise the desired outcomes. As service providers, we really are obligated to ensure our theories make sense, as they inform or underpin the services we offer our clients.

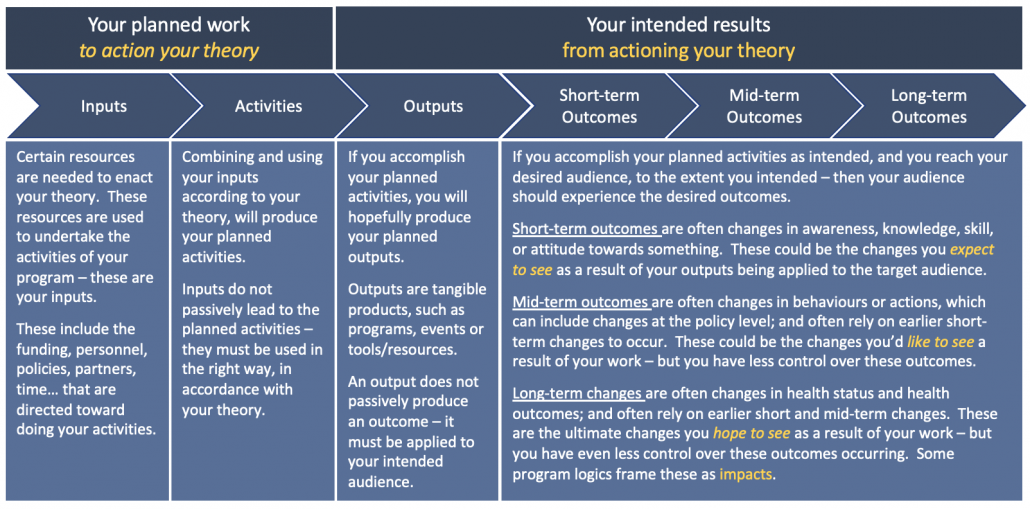

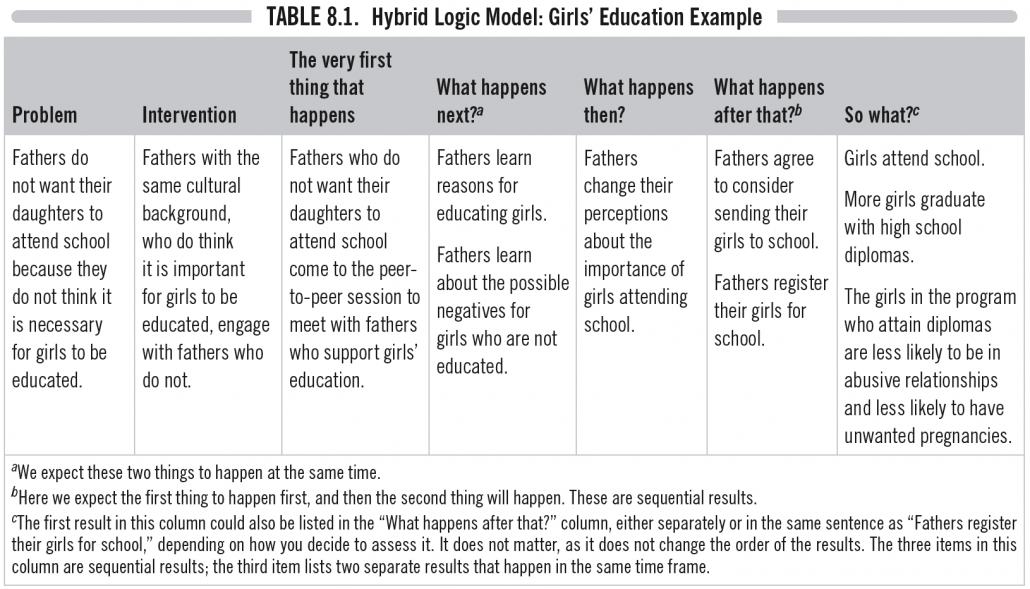

Program logics are really just the plan to operationalise our theories of change. Program logics usually map out (graphically or in table form) the inputs and activities necessary, and the outputs and outcomes we expect to occur, when our theory is brought to life.

Donna Podems, in her fabulous book “Being an Evaluator – Your Practical Guide to Evaluation” presents a hybrid model (see example below), where she incorporates elements of the theory in the program logic. She highlights the prompting question what makes you think this leads to that? as helping to make the implicit, explicit, as we move from left to right.

When was the last time your team spoke openly about your theory of change? Is everyone on the same page? Does everyone understand what underpins what you do, and how you do it? Does everyone have a consistent view of what makes them think this… leads to that?

It’s critically important that they do… otherwise some of your team may be deviating from your program, without even realising it.

Reach out if you’d like to chat more about theories of change and program logics, or if you’d like to more clearly and explicitly articulate your theories and logics – they really are core to the success of your program.