NECESSARY AND SUFFICIENT – LET’S THINK ABOUT THOSE TERMS FOR A MOMENT

We use the words necessary and sufficient almost everyday – but they have a specific meaning in evaluation, and play an important role in Impact Evaluation.

According to Dictionary.com:

- Necessary: being essential, indispensable or requisite; and

- Sufficient: adequate for the purpose, enough.

These absolutely hold true in evaluation nomenclature as well… but let’s take a closer look.

When we undertake an Impact Evaluation, we are looking to verify causality. We want to know the extent to which the program caused the impacts or outcomes we observed. The determination of causality is the essential element to all Impact Evaluations, as they not only measure or describe changes, but seek to understand the mechanisms that produced the changes.

This is where the words necessary and sufficient play an important role.

Imagine a scenario where your organisation delivers a skill-building program, and the participants who successfully complete your program have demonstrably improved their skills. Amazing – that’s the outcome we want!

But, can we assume that the program delivered by your organisation caused the improvement in skills?

Some members of the team are very confident – ‘yep, our program is great, we’ve received lots of comments from participants that they couldn’t have done it without the program. It was the only thing that helped’. Let’s call them Group 1.

Others in the team think that the program definitely had something to do with the observed success, but they think it also had something to do with the program the organisation ran last year in confidence-building, and that they build on each other. We’ll call them Group 2.

Some others in the team think the program definitely helped people build their skills, but they’re also aware of other programs delivered by other organisations, that have also achieved similar outcomes. Let’s call them Group 3.

Who is correct? The particular strategies deployed within an Impact Evaluation will help determine this for us, but hopefully you can start to see an important role for the words necessary and sufficient.

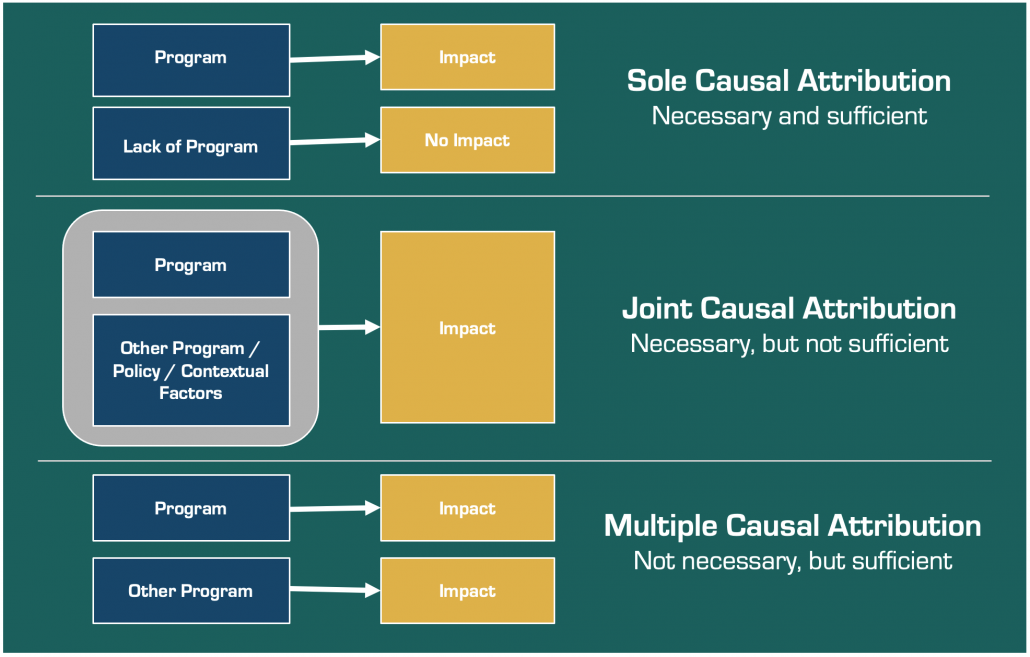

- Group 1 would assert that the program is necessary and sufficient to produce the outcome. Their program, and only their program, can produce the outcome.

- Group 2 would assert that the program is necessary, but not sufficient on its own, to cause the outcome. Paired with the confidence-building program, the two together might be considered the cause of the impact.

- Group 3 would claim that their program isn’t necessary, but is sufficient to cause the outcome. It would seem there could be a few programs that could achieve the same results, so whilst their program might be effective, others are too.

Patricia Rogers has developed a simple graphic depicting the different types of causality – sole causal, joint causal and multiple causal attribution.

Sole causal attribution is pretty rare, and wouldn’t usually be the model we would propose is at play. But a joint causal or multiple causal model can usually explain causality.

Do you think about the terms necessary and sufficient a little differently now? Whilst we use them almost every day, when talking causality, they are very carefully and purposefully selected words – they really do mean what they mean.